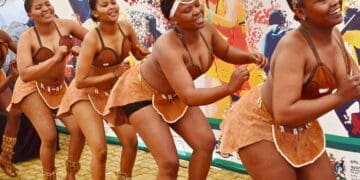

On a narrow plot behind a church in Orange Farm, rows of spinach and spring onions stretch in neat green lines.

The soil is not owned by the farmer who works it, 29-year-old Zanele Msimanga. He rents it for R300 a month and gives the church five bunches of spinach every Sunday as part of their agreement.

“I don’t have land, but I do have hands,” she told Vutivi News.

“I wanted to farm, so I asked around and started here. My neighbours now buy from me every weekend. I make just enough to pay my rent, buy groceries and keep going,” said Msimanga.

Across Gauteng’s townships, a quiet farming revolution is unfolding, one that defies conventional ideas of who gets to be a farmer.

With land ownership out of reach for most, young and low-income entrepreneurs are instead renting backyard spaces, church fields, school lawns and even unused corners of municipal land to start micro-agriculture businesses.

These urban farmers grow spinach, green peppers, herbs and even cut flowers, selling their produce via WhatsApp groups, informal weekend markets and word of mouth.

The model is low-cost, community-driven and increasingly essential.

With food inflation reaching 6.1% in April 2025 and vegetables like onions and tomatoes showing year-on-year spikes of up to 19%, these farms are not just businesses. They are filling a growing hunger gap.

Many of the farmers are women, youth or part-time workers seeking to supplement their incomes. Most operate without access to machinery, municipal water connections, or formal training. They use buckets, recycled grey water and homemade compost systems to stretch their resources. In some cases, they rotate crops every six to eight weeks to maximise yield.

According to a 2024 report by the African Centre for Cities, informal urban agriculture is now practised by more than 16% of low-income households in Gauteng’s townships, and it is on the rise. Yet few of these businesses are formally recognised, funded, or trained.

“We’re not just planting for our own pot,” said Sibusiso Dlamini, a 35-year-old father of two who farms on borrowed land in Vosloorus.

“This is business. I sell spinach for R10 a bunch and make over R1,000 a month. It is small, but it keeps the lights on and sometimes powers the neighbour’s pot too.”

Landlords, in turn, are increasingly open to letting entrepreneurs use their unused spaces. The agreements vary.

Some ask for a fixed monthly payment (between R200 and R500), while others request a share of the harvest or simply agree out of goodwill. As economic pressure tightens, these partnerships are becoming more common and necessary.

But the sector remains fragile. Most of these farmers are not linked to any government support programmes, struggle to access inputs like fertiliser and seedlings and lack formal channels for expansion.

While some municipalities have urban farming strategies on paper, actual implementation has been uneven, with red tape and underfunding hampering progress.

“We need small grants, tool banks, maybe even a cooperative market where we can sell together,” said Msimanga.

“If we had training or access to water tanks, I could triple what I grow.”

For now, the work continues plot by plot, bucket by bucket. These micro-farmers are building businesses from the ground up, quite literally.

And in doing so, they are redefining what South African agriculture looks like: not distant hectares, but backyard beds. Not subsidies, but hustle.