The rising cost of living has changed the way South Africans shop and for many township residents, survival means buying just what they need for the day – five spoons of sugar, two tea bags, or a single cup of flour.

While this trend hasn’t yet hit every corner of the township economy, Soweto spaza shop owner Edwin Mokoena said “customers are no longer buying big”.

“They come with R20 or R30 and want to stretch it, maybe just a small packet of maize meal or a slice of polony. They are buying less because everything costs more,” said Mokoena, who has been running his business for the past 10 years.

Items that used to be considered household basics cooking oil, sugar, flour, and even tea have become harder to sell in full packaging.

“People are cutting down. If something is too expensive, they leave it, or they ask if they can pay me later. Some now prefer cheaper brands or just don’t buy at all,” Mokoena said.

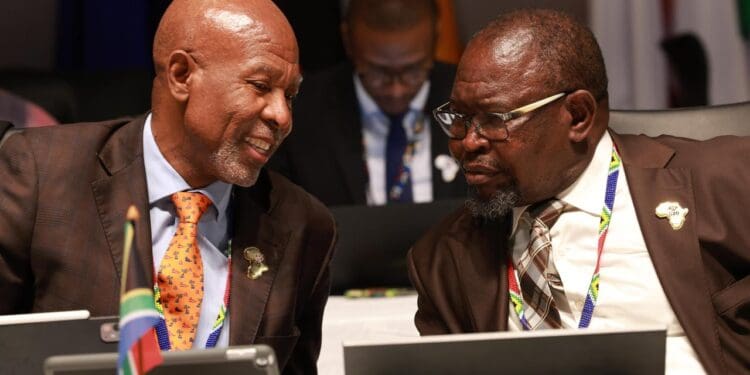

At the SA Reserve Bank’s Biennial Conference last month, Governor Lesetja Kganyago said the current inflation target of 3% to 6% is “too wide” and contributes to long-term price instability.

He signalled that the central bank is looking to revise its inflation targeting framework.

“Low inflation is a necessary condition for sustainable growth. If inflation averages 4.5% per year, prices double every 16 years. That is not good enough,” Kganyago said.

While this may sound like economic theory, inflation hits the streets before it hits the charts.

Small businesses are the first to feel inflation’s pinch — often before the data is even reported by Stats SA.

Mokoena explained that inflation not only affects the customer, but it also puts pressure on him.

“My suppliers raise prices all the time. If I don’t increase my prices, I make no profit. But if I do, customers complain and go somewhere else,” Mokoena said.

Fuel, transport, imported goods, and food prices have all seen volatile increases in the past two years, with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) remaining above the SARB’s midpoint target since 2021.

“We’ve seen flour and oil prices go up multiple times this year,” said Dineo Motloung, who runs a baking business in Mamelodi.

“If I don’t adjust my prices, I run at a loss. But if I do, customers pull back.”

This squeeze is particularly acute for township-based entrepreneurs and micro-enterprises who serve price-sensitive communities.

Peet Marais, owner of Vleismark butchery, has felt the pressure building.

“I’ve had to keep my prices the same because if I charge more, my customers won’t buy from me,” he said. “But that means my profit is much smaller.”

While he has not adopted the practice of selling in micro-portions, Mokoena said it’s something he was considering.

“I would need to change how I do everything, packaging, pricing, even how I store products. But if people start asking for those amounts, I will adapt. If someone only has R5, they must still be able to get something. That’s better than losing a customer completely,” Mokoena said.

North-West University economist Realeboga Mahapa said the trend of buying in ultra-small portions, known as micro-buying, was a direct response to South Africa’s worsening economic conditions.

“Micro-buying is how low-income communities are coping with inflation. It reflects desperation, not convenience. You are no longer buying for the month or week, you are buying for today,” she explained.

According to Mahapa, this shift was also a warning sign for the broader economy.

“When basic food items are no longer affordable in full, and people are buying teaspoons of sugar, it shows just how far inflation has eroded purchasing power. And for spaza shops, it creates new logistical and financial challenges.”

Small business owners are now using apps to track expenses, analyse product margins, and make data-driven pricing decisions. Loyalty programmes, combo deals and smaller product sizes are becoming popular strategies to retain budget-conscious customers.

Sibongile Ncube, who runs a clothing delivery service in Soweto, said clients appreciate being kept in the loop.

“I update my clients monthly on pricing,” she said. “Being upfront helps avoid losing trust when costs rise.”

According to the Reserve Bank’s 2024 Monetary Policy Review, price volatility weakens the rand and reduces consumer spending power. Stable inflation could help reduce borrowing costs and give small businesses more predictable planning conditions. As the cost of doing business rises, adaptability is more than a buzzword but a survival skill.

For many SMEs, inflation is not just a challenge, but a chance to innovate.

“Entrepreneurs should view price stability not as a constraint, but as a key enabler of sustainable business planning,” said Dr Mampho Modise, deputy director-general at National Treasury.

Additional reporting by Basetsana Mahapa